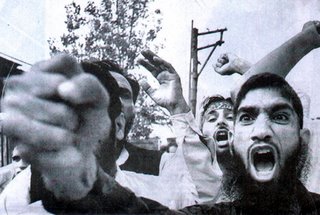

More than anything else, the photograph tells you all… the face of Islam as it protests against the imagined slight from the Pope, heedless of the fact that no offence was intended or in fact given.

More than anything else, the photograph tells you all… the face of Islam as it protests against the imagined slight from the Pope, heedless of the fact that no offence was intended or in fact given.Now, we are told, the Pope has apologised although, as my colleague indicates, the words used hardly convey any regret. And nor should they.

In fact, the last thing the Pope should do is apologise – there has been far too much apologising of late. It is about time the Western world recognised that, when you are dealing with figures such as the one pictured above – face contorted with hate – you do not apologise.

You send them a signal that affirms your own rights and values. If that hatred then turns to violence which threatens our own wellbeing – as it has done – you respond first with counter-threats and then, if the violence does not end, you kill those responsible for it. This is the way it has always been. To pretend otherwise is to ignore history – and the consequences of submission.

The fatal weakness for Western society, however, is that we are rich enough to delegate the killing to our armed forces. And because it is happening – by and large – in far distant lands, we can detach ourselves from it, ignore it or even disown the actions being carried out on our behalf.

However, for us as a society to send off our troops to kill and be killed – and then either to ignore or forget them – is nothing new. Veterans of the Burma campaign in 1945 dubbed their own 14th Army the "forgotten 14th". Conscripts returning from the fighting in the Korean War speak of even their close "mates" being unaware of the reason for their absences and, despite the occasional viciousness if the fighting during the Malaysian insurgency, that too rarely hit the headlines. It was another "forgotten war".

What is different now though, is the global reach of the enemy and its focus on Western civilisation as its enemy. The jihadists are not content merely with expelling what they believe to be foreign occupiers. They are also intent on bringing the war to their enemy.

In times past, defeats in far distant lands would have had no immediate repercussions on the homeland. This was especially true of colonial wars, where actual defeats did occur, which had no measurable effect on the well-being of the domestic population.

Now, enemies that our troops are fighting in Afghanistan or Iraq are the trainers and supporters of our own domestic terrorists and could even become the "fighters" who plant bombs on London tubes or international aircraft. If we lose militarily in any of these far flung places, a newly invigorated and emboldened enemy would not hesitate to strike harder and deeper so, unlike those times past, we stand to suffer the consequences locally.

To win these wars, many things must come together, all of which are inter-linked and inter-dependent.

Firstly, the government of the day must support them – in terms of political support and in providing the resources and strategic direction, against clear and attainable objectives. But those things alone are not enough. The government itself must be committed to winning. It must be prepared to meet changing circumstances and devote all or any resources necessary to winning and must maintain political, media and public support for its actions.

Secondly, there must be the support of parliament, or its least its tolerance. In the absence of both, Members of Parliament can undermine political resolve and, in extremis, bring down the government if it feels strongly enough.

Crucially, in order to keep both government members and the politicians "on side", there must also be the broad support of the media – or at the very least, the absence of a concerted "anti-war" campaign which will weaken political resolve and mobilise public hostility in a way that will affect the electoral base of the government.

Then there must be public support but, again, not necessarily active support – merely the absence of overt hostility of such an intensity that any or all of the wars become significant electoral issues, to the extent that continued prosecution could bring down the government in a general election – or even force a vote of confidence in Parliament.

Finally, for the purposes of this discussion (there are, undoubtedly other issues), the armed forces must have the right leadership, sufficient numbers of trained personnel, the resources and equipment, and they must employ the tactics most appropriate for the situation on the ground.

As to fulfilling all the winning criteria, what we see with Iraq and Afghanistan is an absence of attainable objectives and, stemming from that, the lack of strategic direction. No one is sure precisely what is attainable, in either Iraq or Afghanistan. There is, instead, the vague declared objective of bringing "security" so that the respective elected governments can govern effectively and maintain law and order but the forces on the ground have neither the resources, numbers or equipment to attain that objective.

Arguably – and it is a highly contentious proposition – the government could provide those resources but, given that both the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are unpopular (the former not quite as much as the latter) and expensive enough as it is, to increase those resources might increase the unpopularity to such an extent that resistance stiffens to the extent that they become electoral liabilities.

That the government seems unwilling then to increase the resources to a level where either war becomes winnable, that suggests that it is not actually committed to winning, but is merely going through the motions. It is evidently not prepared to invest the political capital that will ensure victory. And this is where the media comes in.

As a surrogate for public opinion (politicians and the government generally believing that the media does represent public opinion) and with the ability to marshal public sentiment either for or against the wars, the media is crucial.

Given active support for the wars, a good understanding of what is necessary on the ground to win and, and the ability knowledgeably to evaluate weaknesses and demand appropriate remedies, the media is in a position to bolster political and public support. It could, on the one hand, enable to the government to do what it wishes to do to win the wars, but has not done for fear of the electoral consequences, or stiffen its resolve when it fails to take the necessary steps.

In effect, it is probably not an exaggeration to assert that the media are the key to winning these current wars. And, if they are the key to winning, the absence of their support can also lose them for us.

Here there are many problems. On balance, it is probably fair to say that none of the media outlets are wildly enthusiastic about the government having committed our forces to these wars but the general – but by no means firm – consensus is that, since we are committed, we need to win them.

From there it is possible – tentatively at least – to identify where the problems with the media lie. Essentially, there seem to be two. Firstly, the media – rather like the government – has only a vague idea of what the strategic objectives are and then, what it takes – by way of resources – actually to achieve victory.

Perhaps, though, it is the latter that is more important - and certainly more urgent. Given that tactical victories can be sustained, strategic objectives can emerge and be refined in the space created by military success. And, if that is they case, this is where the media are dismally failing.

To offer two egregious examples, both from The Daily Telegraph, the first is an opinion article three days ago from Allan Mallinson, a former Army officer. Under the title, "The Army needs 10,000 more men", he asserts that undermanning in the Army must be resolved, with a rapid boost to the current establishment.

That may be the case – and we would not disagree – but Mallinson also criticises expenditure on equipment projects, many of which are – he asserts - left over from the Cold War. In this, he cites the Eurofighter, asking what is the point safeguarding the skies from a non-existent threat if there aren't enough utility helicopters to fly the Army about a growing number of battlefields? He then continues:

A century ago, pondering the uncertainties of the late-Victorian world, the great historian of the Army, Sir John Fortescue, remarked on a sentimental public tendency: "The popular admiration was not very intelligent, nor was it very helpfully guided by the press.Fine sentiments, but Mallinson, in his current role, is the "press" and while he calls most strongly for more men, he makes no case for the vast range of additional – and expensive – equipment that we need to win the wars. And, as we remarked earlier, men without the right equipment in the right quantity are simply targets.

Neither the one nor the other, pardonably enough, knew anything of the history of the army." Given the events of late, a sentimental, parsimonious tendency is not pardonable today. The habit of success is relatively new, and failure is a possibility. That should be the starting point for the debate the new CGS wants.

Thus do we come to the grand old man of journalism, W F Deedes, who two days ago wrote in his notebook section a lament four our "hard-pressed soldiers". He then writes:

I take note of the Ministry of Defence's assurance that they are now doing all they can to supply the Army in Afghanistan with what it needs, for we are in crisis there. But it cannot give them what we don't possess, such as heavy-lift helicopters.The piece continues in this vein, leaving nothing more than a series of unanswered questions. This is not good enough. To the questions Deedes poses, there are answers – and the answers are known. It is simply cheap and sloppy journalism to take such an easy way out, instead of identifying the problems and demanding action.

There are other items, as there are in Iraq, which the Army ought to have, but cannot expect to get because they are not available.

Has the MoD's procurement policy been at fault, as some declare? Or did the Treasury hold the MoD's purse strings too tightly for too long? Churchill once sagely described the problem of rearmament as "first year, nothing; second year, a trickle; third year, a flood". When did the MoD first become aware of what the intentions of our internationally minded Prime Minister would require of them? How did the Treasury respond?

And, if the Telegraph is bad, none are any better. We have a media which – on current form – had demonstrated that it is incapable of doing a job which, currently, only it can do. It was not always thus. Lord Beaverbrook, for instance, in the days when The Daily Express was the most powerful newspaper in the land, was at the forefront in campaigning for better equipment for the Royal Air Force, getting right down to detail as to which aircraft should be bought, and why.

Putting it all together, therefore, we have a situation now where we not only have a bad media, but one which has within it capability to loose us the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan – which it seems intent on doing.

COMMENT THREAD