It would appear that the Norwegian Nobel Committee shares this blog’s view that there is something farcical about the whole idea of a peace prize. Let us recall the citation. The prize is to be awarded to

It would appear that the Norwegian Nobel Committee shares this blog’s view that there is something farcical about the whole idea of a peace prize. Let us recall the citation. The prize is to be awarded tothe person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity among nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.Well, failing such luminaries of peace congresses as SecGen Annan, Jimmy Carter or Bill Clinton, the committee decided on someone who has actually achieved something though not, perhaps, anything to do with the citation.

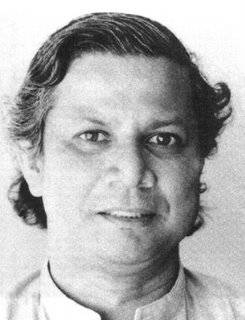

This year’s Nobel Peace Prize went to

Bangladeshi Muhammad Yunus and the Grameen Bank for their efforts to help "create economic and social development from below" in their home country by using innovative economic programs such as microcredit lending.Microbanking may well be a very helpful development. Certainly, in that it emphasises individual entrepreneurship, private property and fiscal responsibility rather than feckless claims of aid money, it has a sense of purpose. One could even argue, as the Nobel committee did:

Lasting peace cannot be achieved unless large population groups find ways to break out of poverty.Since NGO activity and large amounts of aid money are guaranteed to keep people in poverty we look forward to a complete ban of peace prizes or, indeed, any kind of prizes to those organizations. Nevertheless, we cannot help feeling that there is a certain desperation about the award. Best they can do, I suppose.

Meanwhile, I have to acknowledge to have been wrong in my prediction about the Literature Prize. The award went to a man who is reasonably well known, though it is not clear how many people have read him outside Turkey. Furthermore, Orhan Pamuk does not appear to be an anti-American ranter but a man who has tried to think hard and write about the complicated history of Turkey and her even more complicated present and future.

Still, as the International Herald Tribune put it rather delicately:

Still, as the International Herald Tribune put it rather delicately:The Swedish Academy never offers nonliterary reasons for its choices and presents itself as being uninfluenced by politics. But last year's winner, the British playwright Harold Pinter, is a prominent critic of the British and American governments, and the academy does not appear to be immune to the political implications of its decisions.Pamuk is one of those who calls the 1915 massacre genocide, something the Turkish government refuses to do (possibly because it does not want to start paying out compensation to descendants of victims and survivors).

"You're beginning to notice a certain sensitivity to trends - they are giving the prize as a symbolic statement for one thing or another," Arne Ruth, former editor in chief of the daily newspaper Dagens Nyheter, said in an interview. Of Pamuk, he said: "He is a symbol of the relationship between Europe and Turkey, and they couldn't have overlooked this when they made their choice."

Pamuk, who said in 2004 that he had begun "to get involved in a sort of political war against the Turkish state and the establishment," is spending a semester teaching at Columbia University in New York. Nationalist Turks have not forgiven Pamuk for an interview last year in which he denounced the mass killing of Armenians by the Ottoman Empire in World War I. He narrowly escaped prosecution after the remarks were deemed anti-Turkish and a group of nationalists began a criminal case against him.

Interestingly enough, this is an issue that will go on being discussed in Europe as the question of whether Turkey should ever be a member of the EU continues to haunt Europe as the spectre of Communism once did.

The Trib sees it as a coincidence that

on Thursday, one house of the French Parliament approved a law making it a crime to deny that the Turkish killing of Armenians from 1915 to 1917 constituted genocide.Furthermore,

the Armenian foreign minister, Vartan Oskanian, praised what he said were Pamuk's courageous words about the past, in a statement that was bound to irritate Turkey.One can see why many Turks might feel that the prize was not given on the basis of literary merit only, though many others must feel rather proud that one of their writers is being acknowledged in the West.

What of that new French law, then?

Well, France had decided that the massacres should be called genocide back in 2001. What the new law that, so far, has passed only the lower chamber and still needs to get through the Senate, says that it will actually be a crime to deny that this was genocide.

According to the legislation that was carried by 106 votes to 19, anyone denying the genocide would be sentenced to one year in prison and ordered to pay a 45,000-euro (56,570 U.S. dollars) fine.Armenia has expressed herself to be delighted with this development while Turkey is extremely annoyed. To be expected, both of those reactions. The EU has also voiced reservations.

"If this law were to indeed enter into force, it would prohibit the debate and the dialogue which is necessary for reconciliation on this issue," said a commission spokeswoman.This was the enlargement spokeswoman, Krisztina Nagy, who happens to be Hungarian. She also expressed the view that historical events should not be decided by lawyers and legislators but by historians. Exactly what we said about Holocaust-denying.

The EU’s main concern at the moment is the relationship with Turkey and how it will reflect on possible accession negotiations. But there is a certain irony here. Orhan Pamuk was threatened with prosecution and possible imprisonment because he has insisted on calling the massacre genocide. If the French law goes through, anyone who denies that it was genocide will be prosecuted and imprisoned. A neat balance, one might say.

President Chirac has also realized that the Armenian issue is a good one to flaunt if he wants to keep Turkey out of the EU. A couple of weeks ago he went to Armenia and made much of the fact that this was only the second CIS country he has visited after Russia.

While some of his Armenian hosts thought the visit showed their country’s growing regional importance, others were a little less impressed and wondered about the real reason.

"Judging by the deeds and the words of Jacques Chirac [during the visit], his thoughts were in neighboring Turkey rather than in Armenia," commented former Armenian Foreign Minister Aleksander Arzumanian in a 6 October interview with the Russian newspaper Izvestia. "And this is understandable, as now serious problems have emerged between united Europe and Turkey."Mr Arzumanian’s understanding of what is going on in Europe seems to be lacking in substance and subtlety if he thinks that there is such a thing as a “united Europe”, but, at least, he has grasped that Chirac’s thinking is somewhat tortuous. Other commentators have gone even further:

Other analysts see regional issues as motivating the French president’s trip. A desire to compete with Russia and, maybe, the United States for influence in the South Caucasus could be one explanation, said David Hovhannisian, a political scientist and former Armenian ambassador to Syria. Chirac is also interested in Iran, Armenia’s southern neighbor and a longtime ally, with an eye to participation in infrastructure and non-military nuclear projects, Hovhannisian added. Armenian Foreign Minister Vartan Oskanian told reporters after Chirac left that the French president "was very interested to learn" President Kocharian’s opinion about Iran’s nuclear capabilities.Whenever l’escroc Chirac decides to tout France as a power that might compete with the United States and, in this case, Russia, one has to ask oneself whatever happened to the common foreign and security policy.

Richard Giragossian, a Washington-based political scientist, however, argued during a public lecture in Yerevan on 5 October that France’s influential Armenian community rather than any geopolitical factors prompted the trip. This opinion was partly shared by the 168 Zham daily, which said that the visit had acted as "triple PR" - for Chirac himself, for Kocharian and for Armenia, which used the opportunity to tout the country as a foreign investment destination. The trip included a concert for 100,000 in downtown Yerevan by French crooner Charles Aznavour, the son of Armenian immigrants.

Whichever way one looks at it, we are likely to hear a good deal more from France on the subject of those massacres (woops, sorry, genocide). Whether the French politicians really care one way or another is something else again.